Partners in FTD Care: The Heterogeneity of FTD

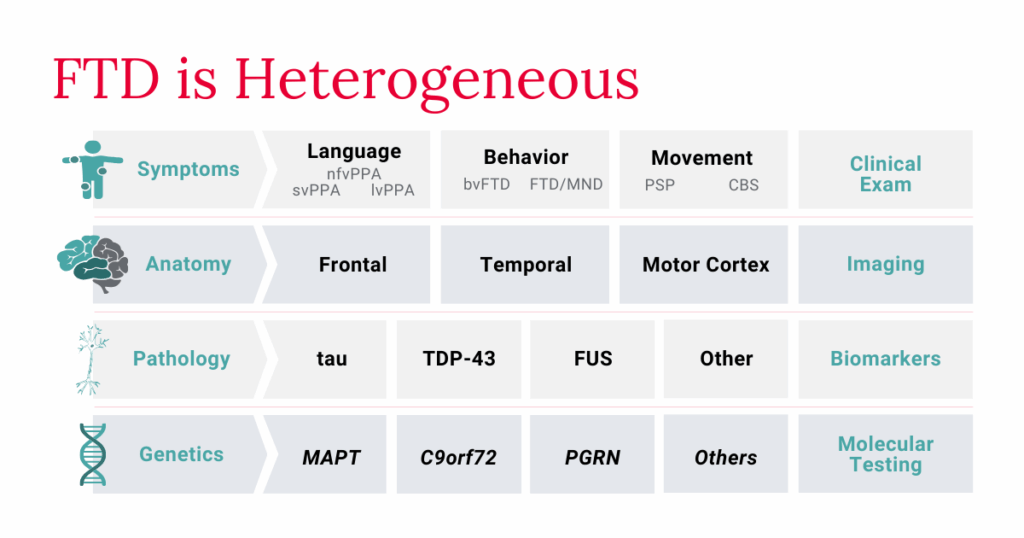

FTD’s wide variety of symptoms present a challenge to healthcare professionals as they evaluate and treat people who either have the disease or are suspected of having it. FTD disorders are highly heterogeneous, meaning there is significant diversity in clinical presentation of symptoms, location of neurodegeneration, and causes. People with the same diagnosis may be affected in different ways.

In order to reduce the time between symptom onset and diagnosis – and to ensure that those diagnosed receive FTD-specific care as early as possible in their disease course – healthcare professionals in various settings need a greater understanding of the complexity of the FTD-disorder spectrum and the variability of clinical presentations.

Clinical Symptoms of FTD Disorders

- Behavioral/Personality: Apathy without sadness, compulsive/ritualistic behaviors, dietary changes, disinhibited behavior, loss of sympathy or empathy, deficits in executive function:

- Language: The gradual loss of the ability to use and understand language (i.e. speaking, reading, writing, understanding what others are saying):

- Movement: Rigidity, dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions), dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), dysarthria (difficulty speaking), gait instability, akinesia/bradykinesia (absence/slowness of movement):

While people with FTD usually first show symptoms of one specific disorder, over time symptoms of other FTD disorders may appear. Someone with bvFTD may, for example, develop symptoms more closely associated with movement disorders such as PSP or CBS. A person who carries a genetic variant that causes both ALS and FTD, meanwhile, may first only show symptoms of ALS, but as their condition progresses, they may also display bvFTD or PPA symptoms.

Managing these diverse symptoms, especially when they overlap, can be challenging even for seasoned healthcare professionals. It is essential to collect a person’s accurate medical history to understand the development of potential FTD symptoms relative to their baseline. Because anosognosia, which refers to a lack of awareness about one’s condition, is a common symptom of FTD (and is often one of the early symptoms to develop), a close family member or friend might be able to best describe to a doctor any uncharacteristic or distressing changes.

Currently, there are no accepted biomarkers for FTD. It therefore cannot be diagnosed with complete accuracy by simply evaluating a sample of blood or cerebrospinal fluid, for example. Instead, diagnosing FTD relies on a comprehensive assessment that includes a complete review of clinical symptoms, whether observed in the office or report by the person experiencing symptoms or a close family member or friend. A tool that can help to diagnose certain FTD disorders is AFTD’s Diagnostic Checklists (below). Physicians can share these checklists with patients and their families to guide the screening process and help families better prepare for their appointment by documenting what symptoms they have noticed. They also provide physicians with a quick summary of the current diagnostic criteria.

FTD Symptoms Reflect Location of Disease Onset

The Role of Proteins in FTD Pathology

- TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43): The most common protein associated with FTD, as well as ALS – half of those diagnosed with FTD and a majority of those with ALS have a TDP-43-based pathology.

- Tau: The second most common protein in FTD – roughly 40% of people with FTD have a tau-based pathology. FTD forms of tau are distinct from those associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Fused in sarcoma (FUS): While not as common as TDP-43, making up less than 10% of cases, FUS is also shared between FTD and ALS.

FTD Risk Genes and Genetic FTD

Approximately 40% of people diagnosed with FTD have familial FTD, meaning that a blood relative has been diagnosed with an FTD disorder, another neurodegenerative disorder, or another similar neuropsychiatric condition. Of those with familial FTD, a specific genetic cause can be identified in approximately 15-20% of diagnoses. Researchers are working to understand the relationship between the specific genetic causes, the underlying proteinopathies, and the clinical presentations of FTD.

To date, variants in over a dozen genes cause FTD, contributing to the heterogeneity of FTD disorders. Most people diagnosed with genetic FTD have pathogenic variants in one of the following three genes:

- Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72)

- Progranulin (GRN)

- Microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT)

Genetic testing can help determine whether a person has inherited an FTD-causing gene variant. Before testing, AFTD strongly recommends genetic counseling to ensure families understand the benefits, risks, and limitations of genetic testing, including what is and is not protected by the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA). Counseling is particularly important when there is a family history of neurodegenerative disorders. Counseling helps families make a well-informed decision about whether genetic testing is the right choice for them.

Researchers are working to identify fluid biomarkers that can be reliably used to identify specific FTD pathologies and their related genetic underpinnings. Several promising biomarkers are being evaluated for FTD5, both for diagnostic purposes and to track target engagement in clinical trials, but they require further study. More research is needed to fully understand variability in protein levels, though tracking changes in progranulin levels is already being used in FTD clinical trials to analyze the efficacy of interventions. A confirmed FTD biomarker can play a crucial role in diagnosis and in clinical trials for potential FTD treatments. Clinicians should therefore encourage families to investigate research opportunities to consider if participation is right for them.

References

- Gordon E, Rohrer JD, Fox NC. Advances in neuroimaging in frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem. 2016;138(S1):193-210. doi:10.1111/jnc.13656

- Bocchetta M, Malpetti M, Todd EG, Rowe JB, Rohrer JD. Looking beneath the surface: the importance of subcortical structures in frontotemporal dementia. Brain Commun. 2021;3(3):fcab158. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab158

- Hofmann JW, Seeley WW, Huang EJ. RNA Binding Proteins and the Pathogenesis of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;14:469. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012955

- Bigio EH. Making the Diagnosis of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(3):314. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0075-RA

- Greaves CV, Rohrer JD. An update on genetic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):2075. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09363-4

By Category

Our Newsletters

Stay Informed

Sign up now and stay on top of the latest with our newsletter, event alerts, and more…