Flooded with Sound, by Tim Ramsey

We first noticed Dad’s hearing loss when he was in his early sixties. He would ask us to repeat things we had said or would answer the questions he thought he had heard.

Dad either did not notice a problem or did not want to admit that there was a problem. Nonetheless, he refused to get hearing aids.

Around the same time, we noticed that he was having a slight bit of difficulty finding the right words to use and completing his sentences. For a man who loved to tell his children and grandchildren all sorts of stories, this was extremely frustrating for him.

He finally agreed to go to the doctor for a checkup. His doctor erroneously misdiagnosed him as an anxious patient with a slight stutter.

Dad was much relieved that the verdict was not more severe and spent most of his remaining days trying to speak slowly and calmly so that he could better express what was on his mind.

His hearing worsened with age as did his ability to speak. His doctor asserted that Dad was just suffering from signs of old age.

We tried to make him feel less self-conscious when he spoke by filling in words that he intended but could not bring forth. But, in time, as his vocabulary was gradually erased, we could barely understand him. We were baffled, and he was frustrated with such limited sentences as: “I put the thing on the thing over by the thing.”

Still, Dad refused to believe that there was a problem. He refused to go see a different doctor. It was only a bad stutter, he reasoned.

An eternity passed as Mom and my siblings and I tried to reason with him. His doctor (fortunately) retired, and Dad agreed to an appointment with a new general physician. That doctor referred him to a neurologist. Several tests were performed that day.

At his follow-up appointment, the physician informed my parents that Dad had a condition known as semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA). He explained that this type of dementia affects two portions of the brain: the frontal lobe (near the forehead) and the temporal lobe (near the temples and ears). Both sections control thinking and memory.

The doctor continued with a description of svPPA. Patients with this type of FTD could expect difficulty in forming words, in completing sentences, and eventually in understanding what individual words meant.

Dad did not have a stuttering problem.

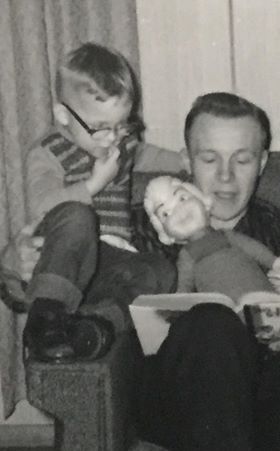

My father, a man of many words, one who loved to read and to share what he read with others, a man who loved to talk to everyone, was soon robbed of the very thing that had brought him happiness for over seventy years. He passed away in December of 2014 unable to say goodbye.

While researching FTD, my siblings and I found some recent studies that have linked hearing loss with dementia. This makes sense as the ears are near the temporal lobe. Studies have shown a correlation between loss of hearing and loss of cognitive abilities.

Here I sit today, less than a year away from sixty. For the past few years, I have found myself asking people to repeat what they have said. This doesn’t go over too well for a teacher nor his unforgiving seventh graders.

I gave in to my wife’s prodding and arranged an appointment this spring with a hearing doctor. The doctor had my wife stand about twenty feet behind me and read from a list of random words. My job was to repeat the words she said.

I failed the test miserably, correctly repeating only fifty-six percent of them.

A few weeks before the end of the school year, I ordered a pair of hearing aids. I returned to school and wondered how my life in the classroom would change. Perhaps silence in the company of adolescents wasn’t such a bad thing?

At one point, I was talking to a boy in my second-hour class about how things will change for him as he prepared for eighth grade. Several times I asked him to repeat what he had said. Somewhere in the conversation, I said, “If I got hearing aids, would you make fun of me?”

“Oh, no, Mr. Ramsey,” he sincerely replied, “I would never do that.”

I received my new hearing aids the day after school let out for the summer. They are much smaller than the devices of my Dad’s day and much less complicated.

Multiple settings can be programmed, and these can all be controlled by my smartphone. I can even stream phone calls and music effortlessly. Ah, the kids will never even know!

I hear things now that I never heard before: A tissue as it presses up against my nose. Plastic bags as they crinkle upon opening. Squeaky doors. Chirping birds. My own breathing.

I even hear my aging joints crackle as I stoop to pick something off of the floor.

A recent trip to Disneyland flooded my ears with all sorts of sounds, so intense at times that I needed to turn down the volume on my hearing aids. I heard tired babies crying with their parents in line for the Dumbo ride. I heard teenagers screaming as they plunged down the plume of Splash Mountain. I heard so many people and birds and motors and announcers and soundtracks – all at the same time.

I could especially hear the words of people behind me – some more than twenty feet away. And I could repeat what they said with excellent accuracy.

In many ways, I am like my father. I love words. I don’t want those words to fade away.

I love to tell stories. I want to be able to forever share those stories with those around me.

I love my family. I pray I never will forget who they are and what they mean to me.

Thank you, wife, for insisting that I go see a doctor. I can hear you much better now.

Copyright, Tim Ramsey, 2018.

By Category

Our Newsletters

Stay Informed

Sign up now and stay on top of the latest with our newsletter, event alerts, and more…